| |

| Photo by Aravind Sivaraj CCx2.0 |

By Jenni

Gate

We drove

down the hill from our home through the city of Kinshasa. Just outside the city, the jungle

was thick. The road was full of pot holes and ruts. Our car bounced along on

the rough pavement, heading towards vast stretches of farm land. About 8 miles

from Kinshasa,

we turned off the road into an open area with several low, concrete-block

buildings spread out around a farming compound. Rice paddies stretched into the

distance, surrounded by jungle. It was the summer of 1970, and we had arrived

at the Chinese Agricultural Research

Center.

The

circumstances of our visit were this: Dad, an agriculturist, was working with a

Taiwanese agricultural mission in coordination with U.S.

efforts to develop rice varieties to help ease the food shortages in Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of the Congo). But

they had a problem—the Congolese people would not plant or eat the rice in

production from the Chinese

Agricultural Research

Center. Dad commented to his

Chinese counterparts that he couldn’t understand why the Congolese rejected the

rice, because all rice tastes the same. The Taiwanese were shocked. The Head of

Station invited all Americans and their families out to the farm to taste the

different varieties being developed.

| |

| Oryza sativa |

We toured

the farm, learning that the land for the project was provided by Mobutu. There

were papaya and mango trees, citrus trees, bananas, and coconuts dotting the

landscape near the driveway. Surrounding the homes and research buildings were

the rice paddies, each marked with signs bearing numbers representing the

variety being produced. The plants looked like long grass in the water, with some

that grew as high as 5-ft. tall. Most of the rice was about 3-ft. tall.

| ||

| Photo: IRRI CCx2.0 |

In one

Quonset hut, we saw many melons, from honeydew to watermelon. At the time, all

watermelons had seeds, so we were impressed when we discovered that the Chinese Agricultural Research

Center had developed

seedless melons. The seeds inside the melons were miniscule, which was great news to me. Dad had always told me

the big, black seeds that I accidentally swallowed every time we ate watermelon

were going to sprout inside my stomach and grow. I didn’t really believe him

but, then again, I had no desire to find out.

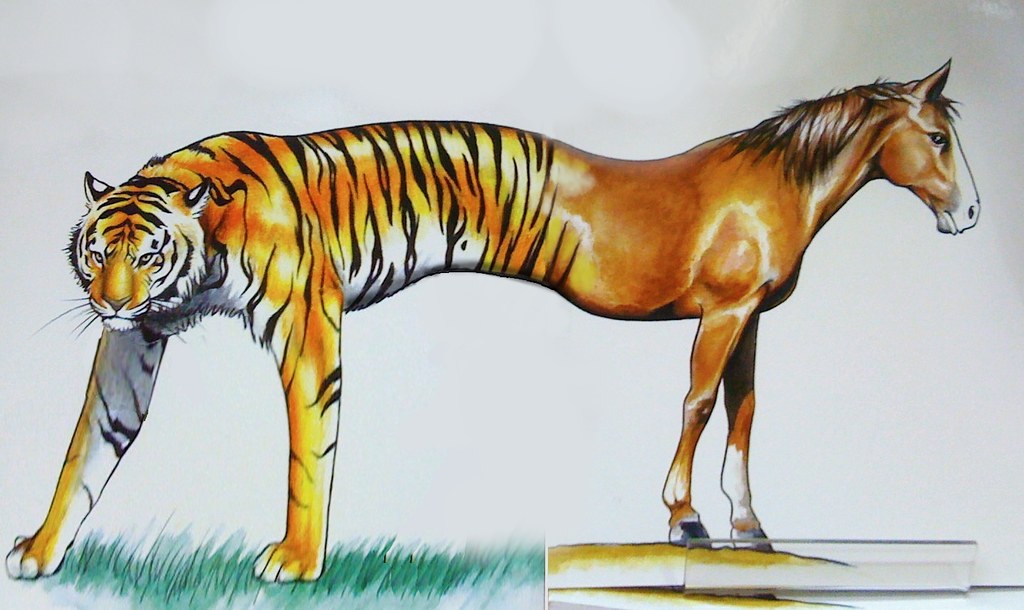

At dusk,

the Taiwanese brought us indoors for dinner. We ate a gigantic steamed fish and a

dish called Lion’s Head Stew, which was ground meat cooked in a rice-pasta

pouch. It was so delicious that I’ve searched for Lion’s Head Stew on the menu

at every Chinese restaurant I’ve been to since then, including when I visited Hong Kong years later. I’m still searching, without

success. Our hosts had us sample several rice dishes of different varieties of

rice. We sampled white, creamy, and brown rice in every shade imaginable. Some

rice was white and sticky and tasted like the rice we were used to eating. Some

of the rice was almost sweet. A lot of it tasted like cardboard. This was the

reason the Congolese would not plant and eat the rice produced by the Center.

The rice available in sufficient quantities for use by local farmers had no

flavor. But there were many varieties still being developed. When we tasted one

variety of rice with a clean, nutty flavor, Dad said, “I want 100 kilos of

that.” Our hosts exclaimed that it was their favorite as well.

| |

| Red, White, Brown & Wild Rice by Earth100 CCx2.0 |

For me and

my sisters, the best part of the meal was dessert. Iced platters, bearing slices

of cantaloupe, honeydew, watermelon, and yellow-flesh watermelon, all garnished

with curlicue shavings from the rinds, were brought out and passed around. The

novelty of melons without seeds kept us awestruck.

It was

summer in Africa, and those melons were sweet

and refreshing.

|

| Photo by Kelly-Wikimedia CCx2.0 |

*****************

As a side note: Years later, Dad took a flight from Jakarta to Hong Kong. He sat next to a young, Chinese man who had been to Jakarta to buy rattan. As they sat talking, the young man mentioned he had been to Zaire. In a flash of recognition, Dad said, “I remember you! You were at the Research Center.” The young man remembered my dad bringing him with us to the Embassy swimming pool on occasion. They exchanged contact information, both commenting on what a small world it is. Indeed, it is.