| Modern Georgian Icons for sale. |

By Edith McClintock

Icons are representations, most commonly paintings, used for prayer and teaching moral and spiritual lessons. They’re widely used in Eastern Orthodox religions and are extremely popular within the Georgian Orthodox Church. Most homes in Georgia display icons in a prayer area—often twenty or thirty devotional images of Jesus, Mary, St. Nino and the Georgian Orthodox Patriarch covering multiple walls.

Icons are representations, most commonly paintings, used for prayer and teaching moral and spiritual lessons. They’re widely used in Eastern Orthodox religions and are extremely popular within the Georgian Orthodox Church. Most homes in Georgia display icons in a prayer area—often twenty or thirty devotional images of Jesus, Mary, St. Nino and the Georgian Orthodox Patriarch covering multiple walls.

Icons are

important in Georgian history and the country’s most beautiful and rare cloisonné

enamel icons, many previously lost or stolen from Orthodox churches in Georgia

and Turkey and dispersed to museums and private collections throughout the

world, are now exhibited at the Shalva Amiranashvili Museum of Fine Arts in Tbilisi.

The 8th-12th century icons are both great works of art as

well as religious relics imbued with nationalistic and religious symbolism and special powers

of healing and miraculous events.

On the

artistic side, cloisonné is an ancient technique first developed in the

Middle East and Ancient Egypt for decorating metalwork such as jewelry. Geometric

decorations were formed by soldering silver or gold strips to metal objects to

create compartments of enamel or gems in a variety of beautiful

colors (see the pectoral jewels of Tutankhamun on left).

In the

Byzantine Empire, thinner wires were developed which allowed more detailed

representations commonly found in icons. Byzantium icons became a highly developed art

form that spread to Italy and Ethiopia and Georgia and beyond. In Georgia, Byzantine

techniques were adapted and became a distinctive school, but both Byzantine and

Georgian icon styles are represented in the museum.

When a

Georgian friend invited me to see the icon exhibit (as she referred to it,

although there were plenty of crosses and jewelry too) at the museum, it wasn’t for artistic reasons. Her interest was religious, which is why

she thought the church rather than the national government should own and house

the icons. She expressed her opinion at great length and volume to our tour

guide while I studied the pretty jewelry, sure we’d soon be tossed out

of the museum.

|

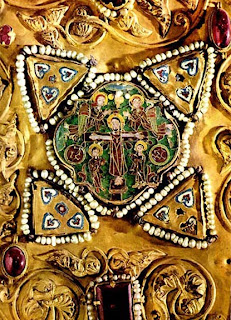

| Khakhuli triptych, Georgian & Byzantine cloisonné enamel, 8th-12th Century |

We weren’t,

and eventually we moved on to the history and symbolism of each icon (usually told with miraculous and nationalistic elements) followed by prayers, although given

it was a museum we didn’t light and leave a candle in front of each icon as is

the tradition in Georgian churches.

According to the

Western Christian cannon, icons in early Christianity were considered graven

images and therefore forbidden by the Ten Commandments. However, they also became

a tool for teaching illiterate populations and their popularity spread. It

wasn’t until the Reformation and Counter-Reformation of the 16th and

17th centuries that the popularity of icons in the West declined,

although less so within Catholicism.

In

contrast, Eastern Orthodoxy teaches that icons have been an important and

unchanging part of the church since the beginning and continue to have deep religious significance.

Veneration of an icon passes to the original so that kissing an icon of Jesus demonstrates love directly to Jesus himself, not just to the representational gold

and cloisonné enamel or paint and woodwork.

But whether you visit the Museum of Fine Arts in Tbilisi for religious, artistic, or nationalist reasons, you won't be disappointed.

But whether you visit the Museum of Fine Arts in Tbilisi for religious, artistic, or nationalist reasons, you won't be disappointed.

|

| Detail of Khakhuli triptych, 8th-12th Century |

| Detail of Khakhuli triptych, 8th-12th Century |

| Ancha Icon of the Savior triptych, medieval Georgian encaustic (made with hot wax painting) 6th-7th Century |

These are lovely works of religious art, Edith. How lucky you were to see them in the museum.

ReplyDeleteThank you for sharing these beautiful icons with us. What a treat to have a guided tour of the exhibition.

ReplyDeleteThese are gorgeous!

ReplyDelete