By Beth Green

When

I moved to China, I half expected my English students to come out

with proverbs as soon as they opened their mouths.

After

all, China’s rich literary heritage goes back thousands of

years―while we in English-speaking countries dabble with our

Beowulf, marveling at the ‘old’ English that was spoken in

700 CE, we should remember that Chinese scholars have been compiling

their own literary classics since around 700 BCE.

Seeing

though, that I would at first be teaching six-year-olds, I quickly

realized that I’d have to look elsewhere for my pearls of wisdom

(even if they were strewn before swine such as I). But, still I had

grand expectations of one day luxuriating in normal things spoken

cryptically―grains of wisdom in everyday conversations.

|

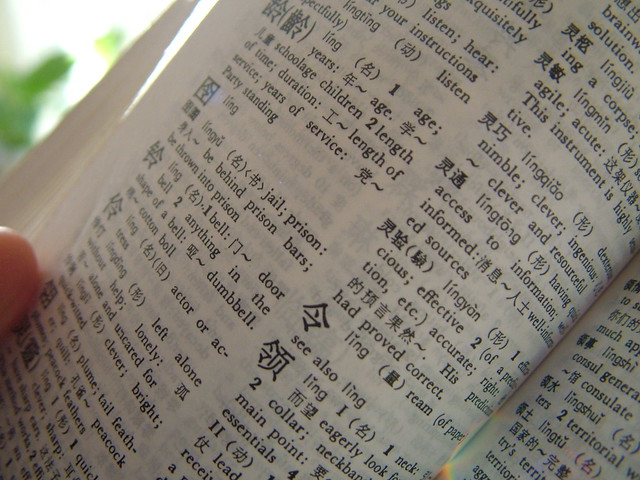

| Image by Ian Lamont from harvardextended.blogspot.com |

I

waited, and waited, and finally came to the realization that, unlike

in many films, Chinese people don’t go around translating their own

language’s proverbs into their second language and using them. This

may have something to do with the way most Chinese students learn

English―rote memorization of set phrases. Instead, my

English-speaking Chinese friends were asking me about how hard it

would have to rain before it would be considered ‘cats and dogs,’

and wondering why a ‘stitch in time’ didn’t save ten, only

nine.

In

fact, I didn’t have much exposure to Chinese proverbs at all until

my second year in China, when my school assigned me a new Mandarin

teacher. (One of the perks of teaching abroad is that often you can

work free language classes into your employment package.)

Serena

and I eventually became very good friends, but in the beginning our

Chinese lessons were rough going. We’d sit in a deserted classroom,

two plastic kid-sized desks edged next to each other, going over

Chinese character stroke order, drilling pin yin

(pronunciation) and working our way through tedious, canned dialogues

from my textbook―which usually revolved around landmarks in

Beijing. Now, I do find the capital of China an interesting place,

but it was about 1,000 miles away, and the lessons on subway systems,

tourist attractions and big-city problems were hardly relevant in the

small town I did live in.

After

a few weeks of boring ourselves to death, Serena came to class with a

thick, dusty, red-covered book she said her father had recommended.

It was a book she’d learned from too, when she was a student― a

dictionary of sayings, or cheng

yu,

成语,

many

of which were only four characters long.

I

was at once both pleased and terrified―finally I was ready to learn

something that was more fun than functional―but at the same time,

if it was still proving difficult to go to the post office in

Mandarin, how was I going to get my tongue (and my memory) around

these, more poetical, set phrases?

Chinese

speakers have used cheng yu (which are best described as

idioms rather than proverbs, though they often impart wisdom as would

a proverb) for thousands of years. Some dictionaries have about

20,000 of these linguistic gems, but Wikipedia estimates that only

about 5,000 of them are in popular use.

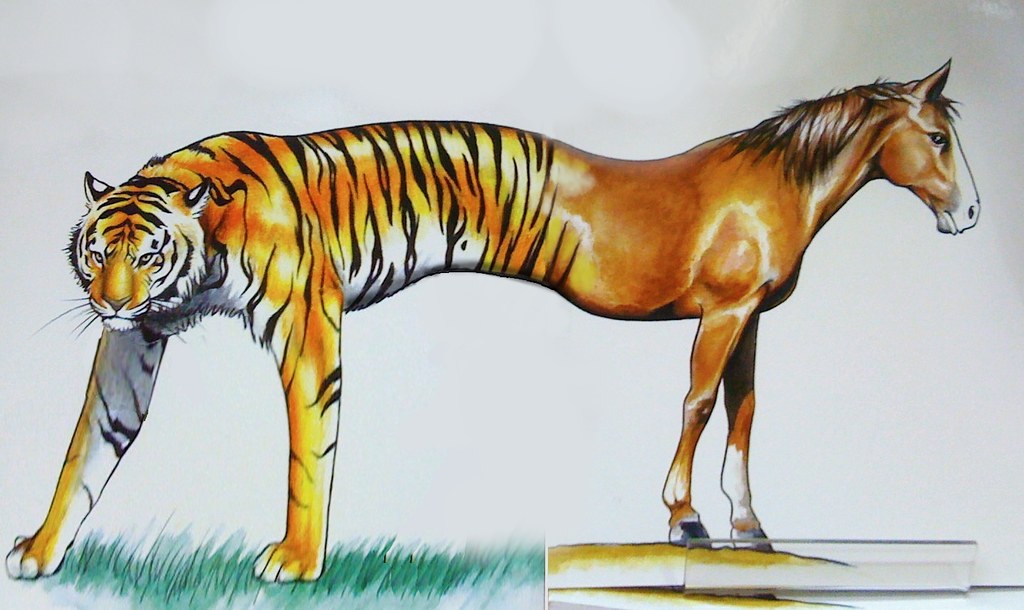

The

first saying I learned (and probably the first idiom most Mandarin

students learn) was ma

ma hu hu (马马虎虎),or

literally, “horse horse, tiger tiger.”

|

| Image by Andrew Scott |

The

meaning however, is closer to English’s wishy-washy “so-so.”

How did the phrase come to mean this? A story I’ve heard is that in

a bad (or so-so) painting you may come across something that’s not

quite a horse, and not quite a tiger.

From

this I went on to learn more sayings made up of easy words. I was

thrilled the first time I found one of the sayings in real life and

not in the textbook. It is a typical phrase well-wishers say at a

wedding: Bai

nian hao he

(百年好合),

meaning ‘may you live a hundred years together.’ I discovered

some of the ornamental chopsticks I’d purchased for my apartment

were engraved with this saying―unknowingly I’d picked up a

wedding set!

I

dearly love Chinese sayings with animals in them. One that a friend

told me recently is this Animal Farm-esque proverb, “Kill the

monkey to scare the chickens” or sha

ji gei hou kan

(杀鸡给猴看).

It means to punish someone as a warning to others.

Another

saying featuring monkeys is this one that immediately conjures a

comical mental image: “a monkey wearing a hat,” or mu

hou er guan (沐猴而冠).

This has a more serious meaning than I first guessed though―it

connotes a bad or worthless person who hides behind their good, or

imposing, looks.

|

| Image by Ganesh Rao |

My

love of crime fiction probably explains why I also delight in the

next two sayings, which have a sinister tone. My all-time favorite

of these proverbs describes backstabbers: “Honey mouth, sword

belly,” or kou

mi fu jian

(口蜜腹剑).

Another good one is xiao

li cang dao (笑里藏刀),

meaning, “a dagger concealed in a smile.”

As

much as I love reading about and learning these expressions, I admit

that I’ve never used anything other than ma ma hu hu in an

actual conversation. My Chinese has never improved to the point that

I could imperil my already fragile and haphazard syntax by throwing

in an aphorism.

In

fact, you could say that, as far as my Mandarin language skills go,

“the rice has already cooked,” sheng

mi zhu cheng shu fan (生米煮成熟饭).

Here is a Hebrew proverb:

ReplyDeleteאם אין אני לי, מי לי; וכשאני לעצמי, מה אני; ואם לא עכשיו, אימתי.

(פרקי אבות, פרק א, משנה יד)

"Im ein ani li, mi li; uchshe'ani le'atzmi, ma ani; ve'im lo achshav, eymatay?"

( Ethics of the Fathers, Chapter 1, Episode 14)

Translation: "If I am not for myself, who is for me? And when I am [only] for myself, what am I? And if not now, when?"

Love the picture of the tiger/horse. What a wonderful rendering of the proverb.

ReplyDeleteits a user friendly website very easy to navigate from mobile and desktop

ReplyDeleteread your favorite quotes by clicking the link below

Love Quotes-

Life Quotes-

Inspirational Quotes-

Friendship Quotes-

Funny Quotes-

Motivational Quotes-

Happiness Quotes-

Good Quotes-

Cute Quotes-

Positive Quotes-

Quote Of The Day